Please feel free to send your own swim stories to the website. ASw is adding chats with various swimmers and campaigners about their own vision and approach to swimming. The first was with Kate Gillwood followed by Caroline Kindy, Joe Stanhope, Chris Romer-Lee, Elias Patel and Safia Bailey. You’ll also find other memories below which have been shared with ASw.:

A Conversation with Safia Bailey

Safia Bailey is a postgraduate researcher at the Welsh Graduate School for the Social Sciences at Cardiff University. She is currently conducting her PhD research into the swimming communities of England’s longest river: the Thames. Her research aims to explore the inclusions and exclusions of this community, the bodily entanglements that arise from immersion into wild waters, and ideas of ecological and human wellbeing. Her research will journey over the course of one year to capture the seasonal variations of these social worlds, using mobile and sensory methods to, quite literally, dive in. She is particularly interested in themes of belonging and becoming, nonhuman entanglements, and ecological and human wellbeing. Her project is titled: A year of immersion into the River Thames: Diving into the seasonal social worlds of river swimming. Her website can be found through the following link: http://riverthamesreflections.org

Photo Courtesy of Safia Bailey

HC: Could I start by asking you a little bit about yourself and how you got this particular interest?

SB: I was thinking about this before our chat and I was like, how have I ended up here? I grew up in Oxfordshire and I’ve always been a river swimmer, really, but more as a kid, you know, it was just playing. And then as a teenager, swimming meant enjoying barbecues by the river and jumping in on a summer’s day, and then gradually I’ve developed this love for the River Thames, which has just grown and grown and grown. I went to university during COVID, so I had limited options for making friends. But the river Cam became a really important place for me to swim, connect with people, to get out of my tiny student flat and just to go and have a change of scene.

So I think I can’t really talk about myself without talking about swimming. That’s what I was reflecting on before this and I think that’s how I’ve ended up doing what I’m doing now. I would say this project has emerged from these personal loves that I have, which include the River Thames, but also outdoor swimming and an acute awareness of the fragility of these spaces that we have and the challenges facing them. I just really love meeting swimmers and hearing of the love that they have for their river, or the anger that they have about the state of rivers, and the power that these communities and their strength of feeling hold. Throughout the past few years of my academic and personal life, I’ve been meeting more and more of these people and I came to the point where I felt I needed to write about them, share their stories and bring them together.

HC: That’s brilliant. Could you go into a bit of detail about your research project and your plans? I can see it involves video data collection.

SB: I’m technically into my second year of my PhD this week so it still feels at a relatively early stage. This project is based in sociology, but I have a background in geography as well. So, at the project’s heart is a fundamental interest in people and place, the two classic things that geographers love. Its central concern is what does the River Thames mean to its swimmers and what do they in return mean for the river? There are these two key aspects that I want to explore, and they sound simple but they are actually huge themes. So, with the video methods that you were talking about, I’m attempting to create an immersive ethnographic journey along the River Thames. Part of that was walking the Thames from source to sea, which I’ve done in June. And then the other part of that is then returning and visiting all these different swimming communities from source to sea.

I’ve found through master’s projects and undergrad that using video methods can just really help to explore the worlds that people are immersing into and to help them reflect on their experiences. It also helps me reflect whilst sat at a laptop, meaning I can start thinking about these themes and places from afar. Video helps evoke places, people, and experiences back to you, even when at a desk. I’m very lucky that my supervisors have a lot of experience with GoPro and mobile methods, so I’ve also been inducted into this with a lot of support. So the central focus of the project is these immersive methods. They are really important to me in terms of listening to the river and listening to the swimmers at the same time, because for me the river is as much a character in my research, as its swimmers are. They’re both equally important. It’s weaving these together and video for me is one way to begin doing that.

Photo Courtesy of Safia Bailey

HC: Fantastic. Just out of curiosity, what’s the length from the source to the sea that you walked?

SB: I believe the Thames itself is 215 miles. I walked the Thames path, which is a publicly accessible national trail and that was 232 miles because there are some diversions away from the river. I walked through June from source to sea and the source is in Kemble, which is Gloucestershire and then I was on the South side, so I ended in Kent where the Thames feeds into the North Sea.

HC: Wow. I was looking at your main supervisor’s profile (Dr Charlotte Bates) and she’s written a lot on swimming which was a good discovery for me. The idea of inclusion and exclusion in terms of swimming communities seems relevant to your work. I’m just wondering, what are the different types of swimming communities that you will encounter?

SB: I think this is something that I’m only just discovering and that I will have to revisit as the project unfolds. But this is partly a kind of reflection of the communities that live alongside the River Thames. For example, a lot of the upper Thames flows through the Cotswolds which are often home to middle class communities and, typically, quite white communities. So, in the upper reaches of the Thames, these are the groups of people you might find swimming. These communities also often involve a lot of women, like myself, which is reflected as I’m sure you know, in a lot of outdoor swimming communities generally. But with this recent call for my project that you’ve seen in Outdoor Swimmer, I have had such a wide range of people contact me, which has been amazing and is such a reflection on their readership. I’m quite intrigued and hopeful to see just how inclusive the Thames outdoor swimming community can be. Currently I don’t necessarily have a strong answer to your question and it’s something I want to go in and explore as this project unfolds in the coming year.

HC: I recently I did a couple of swim events in London that were parallel to the Thames. One was the Dock2Dock, but I remember telling people I was going to swim in London, and many frowned at me. And I said, well, it’s not actually in the Thames. It’s just water beside the Thames. So, when you follow your journey, are you thinking in terms of what counts and what doesn’t count as ‘swimming in the Thames’?

SB: I am. My focus is on people who are getting into the river, but I’m also really aware that there’s places such as central London where it’s much harder to do that for various reasons, whether it’s extreme pollution or just simple water safety. So, I’m actually just as interested in those places where maybe we can’t swim or there are barriers to swimming in the main river itself. I’m interested in how people are continuing to swim or finding ways to swim when it’s not possible to do so in the Thames. I’ve had various people reach out to me from the docks and I would be very interested to explore that as a place where people are connecting with water in London. I’m not wedded to the Thames itself, but am also interested in how people are engaging with water in and around the Thames, especially in places where they cannot necessarily access it.

Photo Courtesy of Safia Bailey

HC: That sounds great. So, back to the environmental side of things. I live in West Yorkshire and the river that flows through the town I live in is the Wharf. Particularly during COVID, I found myself swimming in it a lot as soon as the swimming pools or other venues shut. I was in the Wharf as quickly as I could, but over the last few years year I’ve not been swimming there just because concerns over pollution. Is this something you are encountering?

SB: Yeah, absolutely. And a very powerful thing about the walk was meeting people who aren’t swimmers. And when you’re carrying a big bag, a lot of people stop to chat to you. So I had a lot of conversations along this journey and would tell people what I was doing. And there was a lot of kind of shock or just general advice that you shouldn’t be swimming in there. It’s dirty or it’s dangerous. Part of what I am keen to do through this project, whilst being acutely aware and sensitive to the risks that outdoor swimming involves and the potential for sickness, is to foreground how for so many people this is a rejuvenating, restorative, joyful thing, and how so many of those swimming communities do continue to exist despite the challenges they face. And I think that’s incredibly important to spotlight these communities and show that they are there, especially when our rivers are under such threat. I think it’s a very powerful thing to have these people who are often in a very intimate relation with their river because they are getting into it and sensing everything that’s there and seeing it and feeling it, often through the seasons.

So, I think part of it is acknowledging that these are kind of murky, dirty, polluted waters, but that they also offer swimmers so much. And that’s partly why people are still doing this despite the risks. I feel it’s important to speak about the pollution and the threats facing these freshwater bodies, whilst at the same time it’s important that that’s not the whole narrative. And I think again walking the Thames, I was just overcome with the amount of beauty and thriving life that I observed along that journey. And I came back and told people I’d seen otters and seals and they couldn’t believe that because it’s contrary to the Thames that so many of us have in our heads. Actually, there’s so much there that is still worth protecting and saving and restoring, and I think swimmers are a part of that narrative for me.

HC: Yes, I agree completely. And I think by doing the research that you’re doing, hopefully that will make the river less murky because the value you’re highlighting is the significance of the water to so many people’s lives. And it gives further impetus to people to say, you know, let’s look at ways that we can clean the river up and make sure that it’s being used in the right way. Every summer are stories in the news about teenagers or younger children drowning in open water and often it’s in places where the water is cold. And there’s a reluctance to have people gain experience in those kind of swimming conditions. With that experience, you could definitely reduce the number of these incidents where people lose their lives or get injured. I think having a message that says the river is polluted just don’t swim there. That is completely defeatist.

SB: I completely agree. I grew up in a village and we swam every day after school in the summer and maybe not in the wild swimmer kind of way, but more in the way that we were kids and we wanted somewhere to play. I think increasingly, with climate change, not just kids, but everyone is going to need these spaces. And I do think it’s so important that we think about how we can safely, or as safely as possible, connect people with the places that they will be visiting anyway.

HC: Yes. I like swimming pools, but you can’t always go to a swimming pool and spend money on an admission ticket and go through the changing rooms. But if you can just run around the corner and there’s a river or a lake, then that’s a different thing altogether.

SB: No, exactly. I’ve been in London a lot this summer, and when there are heat waves, swimming sites get completely booked up. I didn’t know this was a thing. So, I think there’s that other thing when swimming is just there and it’s free and you can, like you say, walk down. That’s magical.

HC: I like that you’re exploring the deeper connections with people’s lives as well because the connection that we have with our environment is absolutely crucial to our well-being, to who we are, our sense of identity and if there’s an imbalance and the environment is being degraded, then I think it really has an impact in so many different ways. So, what’s your schedule for data collection? I imagine that’s probably starting soon.

SB: Yes. The walk happened in June, which was kind of the big start and then I’ve begun slowly meeting swimmers ever since. But that’s beginning fully in the coming months – through this autumn, depending on weather conditions and if the river is too polluted to swim in. Thanks to Outdoor Swimmer, I have begun to build up a very nice source to sea map of these communities, which is amazing and super exciting. From autumn, swim-along interviews are beginning and then, ideally, and if this works for participants, I would love to revisit them over the seasons of one year and explore how they engage with the river over those seasons. That might not always involve getting into the river together. It might be sitting beside it because it’s full of sewage or it’s flooded. I’m just fascinated by how swimmers connect with the Thames over the seasons of the year. So, these swim-along interviews will take me from this September to summer next year.

HC: That’s fantastic. That sounds so exciting. And in terms of the swimming communities that you are mapping? What’s the distribution? Are there, huge distances between them? Are they clustered in particular areas?

Photo Courtesy of Safia Bailey

SB: I mean, I’ve been so surprised. I came away from my walk a bit worried that maybe there weren’t that many swimming communities left because of what people have said to me and I’ve been so happy to get a really nice spread of participants from source to sea. There is a natural gap in some parts of the estuary where currents make it too dangerous to swim, and there are also challenges in central London although there are plenty of swimmers in the docks. But I will be working with communities all the way from the source in Gloucestershire to the saltier waters of Essex and Kent which is really exciting. I’ve been very lucky and am very grateful for the response from Thames swimmers, who I’m excited to get to know from source to sea.

HC: Well, it’s fascinating research and I can’t wait to see as you begin to write and publish. Thank you so much for talking with me today.

SB: Thank you.

A Conversation with Elias Patel: Goa Open Water Swimming Club

Elias Patel is one of three founding members of the Goa Open Water Swimming Club and I had the pleasure of hearing about the work that he and his colleagues do through their club. Further information can be found at their website: https://www.goaopenwaterswimmingclub.com/home

ASw: I wish I were in Goa right now, so I could go swimming.

Elias: It’s not that far, it’s a 10-hour flight, so anytime you decide to come to this part of the world, and you want some warm tropical waters with a few exotic jellyfish, just give me a call, and we’ll be happy to have you with us.

ASw: Fantastic. Do you mind giving a little bit about the history of the club? I know that you were one of the original people that helped set it up, but that would be great to hear about that process.

Elias: Yeah, sure. So, it started back in 2015. It was a group of people that just decided to swim on Sunday mornings after a late Saturday evening at the pub. We used to eat late in the morning at around 11 o’clock in the morning, and then we used to just have a little bit of a recreational swim, not too far, maybe 300-400 meters. Uh, and then just mull around the sand and meet for a couple of beers and some fresh fish, which is a speciality of Goa here. And what started off as a recreation and a hobby slowly started turning into curiosity. We had people walking on the beach looking and saying, ‘Hey, what are you guys doing?’ And in this part of the world, in the subcontinent, swimming is not something that comes naturally to most people, because from a young age, people are told that the sea is dangerous, and you shouldn’t go into it.

All photographs courtesy of Goa Open Water Swimming Club: (L to R: Elias Patel, Nicole Pavri, Meenal Kansara)

It’s largely a cultural thing as well and so when they saw a bunch of brown people, (they were used to seeing white people in the water), they started getting curious saying, ‘Hey, what are you guys doing, and what’s happening, and how is it working?’ And a whole lot of questions that started coming up as a result of that. And what started off as a small group of people slowly started snowballing into more and more people over a period of time. And fast forward to today, we have about 4,000 people who are now members of our club, which started off with, like, just about 6 or 7.

ASw: That is amazing! 4,000! That’s absolutely brilliant. And I get a sense from the photos on your website that you’ve got a range of ages and abilities.

Elias: I always say the sea doesn’t differentiate. It welcomes people of every ability, of every nationality, skin colour, gender, it doesn’t matter, right? All that it asks is that you respect it. And that’s all. And for us, that was a large part of transitioning from the culture of fear and the culture of the unknown, to a culture of understanding, science, and respect. And that’s what we wanted to do, is to change that mindset to respect… of course, it’s an extremely powerful force, we know what it can do, but at the same time, it’s not something that you blindly fear out of superstition or out of lack of knowledge.

ASw: There’s certainly parallels with here in the UK where every summer there’s often teenagers and young children that drown in rivers or in reservoirs because the opportunities for them to learn about open water swimming are becoming less and less, and so basically, you just get a sign saying, ‘No Swimming’, and people think that’s the problem is solved. On hot days, when we have them, people who go in, they’re not used to the shock of cold water, and we have young children that drown, and it’s because they’re not really receiving that kind of training to learn and respect the water, but also to how to use it.

Elias: Absolutely. I mean, more than 70% of our planet is covered with water, and I think it’s essential that every human being learns how to swim. I think if you take any mammal, and you chuck it in the water, it’ll swim. Why can we not swim? It’s largely because of fear, it’s because of a whole lot of things. That has been drilled into our heads from a young age so that creates a barrier, and we need to start overcoming that barrier with the right kind of training, which, by the way, we put ourselves through every single year. So, all my instructors, we have 14 instructors right now, we’re all trained in first aid CPR, and we get into the water during the rainiest, the most choppy conditions during the year. We have waves which are, like, 18 to 20 feet high coming at us, but we drill in that time, because if you can look after yourself at that time, you can look after others in a pond-like condition.

ASw: That’s brilliant. One of the things that I really enjoyed on the website was a really nice story by Nusheen Nalwala about participating in the 20K relay. You had some swimmers that were doing the whole 20K on their own. And then she was doing a relay with 4 people, so she was doing 5K, which is very good. I’ve never done 5K. I’ve just signed up for a 3K event. But she also writes about the ‘chop’, and the jellyfish, but I really enjoyed reading her story: https://www.goaopenwaterswimmingclub.com/about-us/our-blog

Elias: So the 20K swim was an extremely interesting challenge. We always wanted to do a 20K swim. The maximum that we’ve ever organized was 10 and it was a dream for us, because we are lucky in Goa, we have one of the longest uninterrupted beaches in India. Almost 31 kilometers of beach from the northern to the southern end. And we thought, hey, what better way to showcase Goa than to swim along a large portion of that beach. So, we started marketing it. For us it was a learning experience because we had never done it, so it was a whole lot of researching and getting our safety in place, and for us, safety is paramount. You know, everything else comes secondary, so we need to make sure that every single swimmer in the water is looked after at all times. Whatever the necessary safety measures are, we do a calculation and then we double it. Just to be safe, right? Which is why sometimes you don’t end up making money, because we end up spending everything on lifeguards, jet skis, boats. But that’s fine. We do it because we’re so passionate about it.

And the great part about that swim is it had never been done in India before. We were the first people to put it together. We were recognized for it. There are a few articles that were covered across the country about what we did. We had people of different abilities coming for it. We had a group of people who are planning the English Channel next month They wanted to do it as a kind of a training experience, so we had them coming. We had people who were doing the Catalina straits in California coming for it. We’ve had people from different parts of the country, and also a couple of people from abroad, just flying down to Goa to be a part of this. It was very, very exciting. It took us almost, two and a half to three months of planning, and the entire thing was done in 8 hours.

ASw: That is great. And I noticed that it looked like some people were wearing wetsuits, and some people weren’t. Is that for protection against jellyfish, or is that temperature?

Elias: No, so it wasn’t really a wetsuit. What it is, is what we call a bodysuit or a rash guard. It’s non-insulated. There’s zero insulation on it. We don’t allow wetsuits in this part of the world because of the heat, obviously, and we have the opposite of what you guys have. You all have hypothermia, we have hyperthermia, which is overheating, and it can happen pretty rapidly with the sun, once the sun comes out. So we don’t allow wetsuits out here.

Asw: That makes sense, yes, I’m going to do the ‘Great North Swim’ in the Lake District next month and I think most people will be in wetsuits, because it’ll be about 10, 12, 13 degrees. But it’s good, because you get the buoyancy from a wetsuit. You go a little easier swimming in the wetsuit.

Elias: That’s true. It makes it easier.

ASw: As long as it’s not rubbing your neck and things like that. You have to get used to it. It feels a bit weird, yes.

Elias: Yeah, so what I would suggest you do is use it for about a week to 10 days before your swim every day. Let your body get used to it, and then go for the swim, right? Don’t let it be a brand new thing that you put on.

ASw: Exactly. In Nusheen Nalwala’s blog, I got the sense from her of what I thought was really lovely in how she was thanking everybody that was participating, and not just the other people in her group, but the kayakers, the lifeguards, and you really got a sense of the amount of work that goes on to do an event like that.

Elias: It was quite funny. In fact, this time, we had 18 people in the water, and we had more than 18 people to support them. Every single person swimming had their personal lifeguard, their own jet ski, kayak board, it was quite interesting.

ASw: That is amazing. Here in the UK, there’s a lot of open water swimming with a connection to environmental concerns because we’ve got issues with our rivers, they’re really polluted. We’ve got issues with our lakes; we’ve got issues with the sea around the UK. There’s a river that runs right through where I live, and I used to swim in it, and I don’t now, because the pollution is just too bad. Are you fortunate around Goa to have water that’s cleaner, or do you have to raise environmental awareness as well.

Elias; So, traditionally, Goa had pretty clean waters. When I say traditionally, I’m talking about maybe 40, 50 years back during our parents’ time, right? Unfortunately, what’s happened is we’ve had a lot of growth oceanside, a lot of hotels coming up along the beachfront. We have a very unique phenomenon in Goa where we have floating casinos in the river. These are boats, almost the size of a ship which are casinos, and which are in the water. And a lot of them pump effluent into the ocean and into the rivers, and what used to be really clean waters 40 years ago is not that much anymore, right? So we are facing those problems. We are definitely facing pollution at levels that we’ve not seen before. From a South Asian point of view, if you look at it, it’s definitely better than many other parts of the country, because we have a far smaller population.

As you know, India is now the largest country in terms of population, right? But it is still a cause of concern, and what we are doing here is, to answer your question, is we have a lot of work with government bodies now and we work with the municipal council of Panjim for cleaner waters. In fact, we are charters to the Swimmable Cities Project, which is happening in Rotterdam and we signed up with them and we also do a lot of outreach programs to schools and colleges where we start at the grassroot level, making people understand that that plastic bag is not just a plastic bag. It goes into the ocean, and you end up swimming in it. But that only happens once you start swimming, you realize the impact of what you’re doing, right?

People thought of this ocean as this big thing where you can’t see it. What’s kind of out of sight is out of mind. But now you’re seeing all that crap coming back on your beaches, and you see it even more so during the monsoons here when the seas are so choppy. You find things from different states being pushed onto our beaches, and it’s not a pretty sight, to be honest, but I am quite hopeful about the way things are changing, especially with the new generation. I have two young kids of my own, I have a boy and a girl, 7 and 4, and I can already see the difference in that generation, you know, there’s so much more awareness of things. They won’t use plastic, they want reusable stuff. Even a banana peel, we were on the boat the other day, and some guy threw a banana peel, and we have this thing about fruit being biodegradable and going into the ocean, but even things like that, banana peels are not something that fish are used to eating. So you’re putting things which are not in their food source in the ocean. So, then we would say, ‘No, hey guys, don’t do this, or be careful, or take your trash back with you.’ So, I think things will change. It’s gonna take a little time, but I’m hopeful about it.

ASw: That’s good, it’s really nice to hear that hopeful message as well. I went to a small protest, this weekend. It was organised by Surfers Against Sewage which is a big organization here. There was one in Leeds and leading right up to the day of the protest, Leeds, wasn’t going to be involved, and then it was young people, a group of largely women around 20 years old who took it upon themselves to organize. I went down, and it was good to see people out there trying to raise awareness about pollution in the rivers, and it was young people doing it.

Elias: I’ll tell you, that’s the generation that we need to look at, and I’m pretty hopeful. I think they’re going to do what we couldn’t.

ASw: Yes, I hope so. And you mentioned ‘Swimmable Cities’. That’s actually where I first saw your club mentioned. https://www.swimmablecities.org/

Elias: It’s interesting, if I tell you this, you won’t believe me, but we are the only teaching club in the country right now. A country of 1,200 million people, not even half a percent can swim, and out of that half percent, I don’t know how many can actually swim in the sea.

ASw: Wow.

Elias: The rates are really low, but in terms of potential, it’s huge. Every year, we train about… 500 to 800 people, who then go back and make a difference in their communities. And for us, that’s what it’s all about. And in addition to that, we also run the Goa Swimathon which happens in the month of February. It started off in 2011 with just a bunch of people, around 8 to 10 people decided that they want to swim. And we said, okay, let’s do it for fun, right? And we swam across a little river, about 5 kilometers recreationally. And over the years, it’s reached a point now where it’s one of the largest in the country. We get about a thousand people that come every year. And we have it over a period of 3 days. We have a 1, a 2, a 5, and a 10 kilometer swim. And in addition to that, we also run a triathlon called the Goa Triathlon, which is swim, cycle, run, Olympic distance. So we have a pretty busy calendar throughout the year, but it’s a lot of fun, and a lot of engagement. We’re lucky that we have the state government that’s supported us in our endeavors. Yeah, it’s pretty exciting.

ASw: Well, it sounds like you’re doing absolutely brilliant work. I guess a final question is what do you see kind of the biggest challenges ahead for the swim club. I mean, it sounds like you’re just going from strength to strength, and everything is looking rosy, but are there any challenges that you see over the horizon?

Elias: I think what we have been seeing over the last few years is the amount of jellyfish that we’ve been noticing and that can be a challenge because when people go out into the water, when they go out to swim that is something that they don’t want, right? They don’t want to get stung, they don’t want to have this unpleasant experience. And we sat down on a scientific level, and we said, let’s understand why there is this increase in jellyfish, right? It can’t just be coincidence, there must be a reason. And so, we got into the nitty-gritty of it, and we realized that obviously our oceans are becoming more acidic. The oxygen levels in the ocean are dropping, but that of course is something which is a global phenomenon. But on a more local phenomenon, we’ve noticed a significant drop in the number of turtles that we have in Goa. Over the years, and you know, turtles are the chief predators of jellyfish. And if you take the predators out of the equation, the prey goes through the roof, right? So, we are currently working on a turtle conservation program as well, where we’re getting the turtles back. I’ll send you a couple of videos where we go to a beach where every day during the season, we release about 80 to 100 hatchlings back into the water. Turtles are our hope now.

We hope that they can keep the jellyfish population under control. They were always part of our Goan beaches. But, pollution, poaching, a whole lot of things, have led to a decrease in numbers. But I think, the jellyfish, for sure, and pollution is another thing that we need to keep under control. If these two things can be managed properly, then I really don’t think there should be any problems.

ASw: Well, I think you’ve just raised my appreciation of turtles. I mean, anything that’s hardy enough to eat a jellyfish is amazing.

Elias: There you go, absolutely. They’re not the tastiest things on the planet, we just got back from Malaysia yesterday, and I, and we thought we would try some. No, they’re not tasty.

ASw: I’m doing a swim in Turkey in August and it’s mentioned that there’s jellyfish, and as a kid, I was stung a couple of times, and I kind of vaguely remember it, but yeah, I’m not looking forward to being stung.

Elias: Yeah… A lot of times, it’s the fear of the unknown, right? Once you get stung, you realize, okay, it’s not that bad. Or shit, it was worse than I thought. Depends on the species. I think that’s pretty much what it is for the future, and I hope that good things can happen.

ASw: Well, thanks again so much for your conversation today. It’s been a pleasure talking with you and learning about your fantastic work and the swim club.

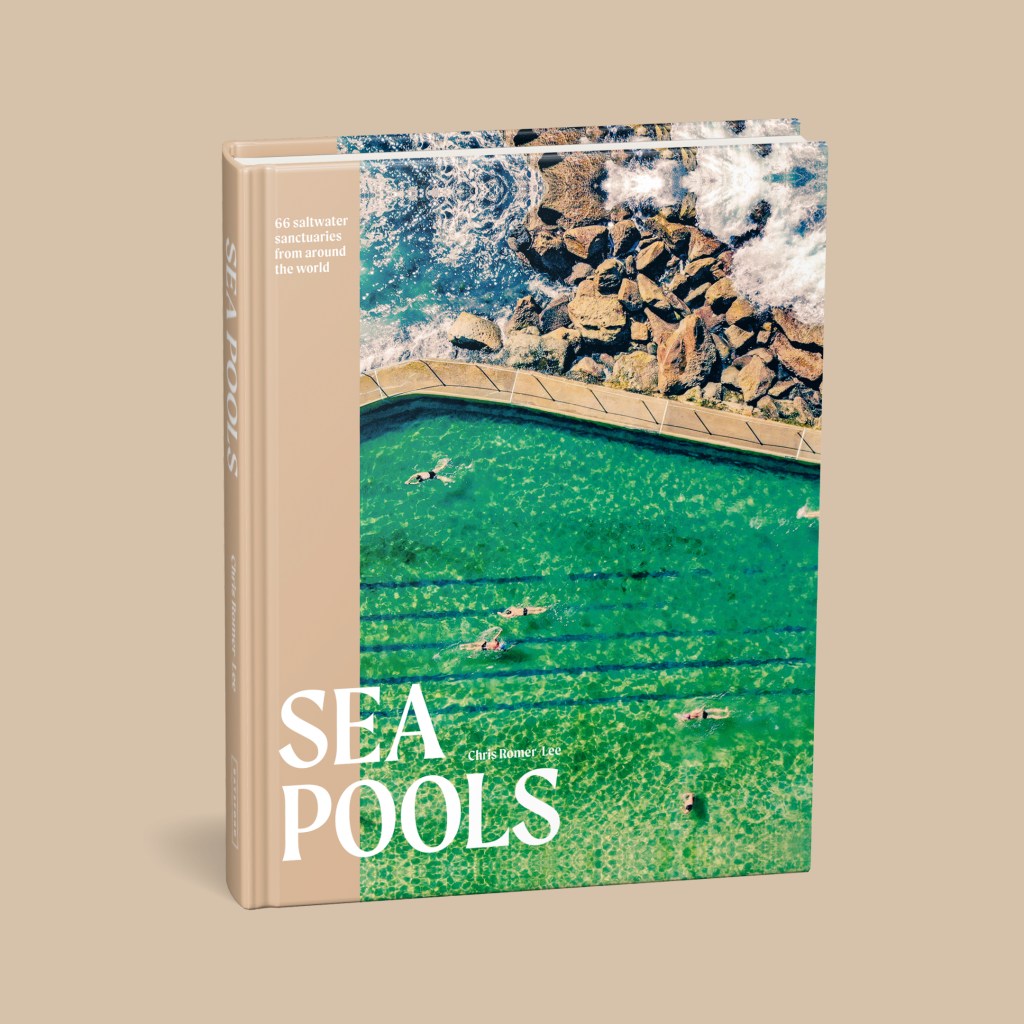

A Conversation with Chris Romer-Lee: Sea Pools, Future Lidos Group and Studio Octopi.

Haynes (H): Let me start by asking your original attraction to swimming and pools in general.

Chris Romer-Lee (CRL): I think it all started off really from, Thames Baths, which was a proposal for a floating lido in the Thames about ten years ago and that project still rumbles on. On Friday I saw that ‘+ Pools’ https://pluspool.org/, which is a campaign for a floating pool in New York that inspired Thames Baths (That’s been going slightly longer, I think 12 years) got permission from the city authorities. So that’s exciting for Thames Baths, but it kind of started off there and that was the trigger for me. Reflecting on my younger years, I realised that my parents had taken me swimming or taking us to water pretty much every holiday, whether it was a canal boat holiday, a beach holiday. We’d always end up on the coast or on the lakes in Italy or Mediterranean or wherever and I hadn’t really thought about that before. And it was on the back of Thames Baths that I really got back into swimming outdoors, joining the Serpentine Swimming Club just before Covid, which actually was very lucky because it was a brilliant thing to do through Covid. So I guess that’s the introduction to water and my obsession with it now.

H: I’m thankful to you for writing Sea Pools because I hadn’t thought about tide pools as a space for swimming and because I don’t have easy access to the coast. But in terms of inclusivity, they are the ultimate place because people can, in theory, swim without restrictions. What got you interested particularly in sea pools?

CRL: Well, very bizarrely, and again, I hadn’t really clicked since I started to write the introduction. The very initial proposal for Thames Baths was a tidal pool, so it used the six-meter tidal range in the Thames in the centre of London to refill the pool with ‘fresh’, [fresh in inverted commas] Thames water. But it was also based on the proposal for when the ‘super sewer’, which is a new sewer underneath the Thames which is going to stop 96% of the sewage overflows. So it was a vision of like, hey, when the Thames is clean, why don’t we swim in it? I then began to look at tidal pools across the UK, including the ones I’m familiar with like Walpole Bay in Margate. That’s the largest one in the UK and is a marvel. I then found them in Cornwall and Scotland.

And I began to draw little patterns and threads between each of them as to why they were occurring in certain places and not in other places. But then I’d think, oh, well, you know, Brighton’s got a very steep beach. It’s pebbly. Why isn’t there one on Brighton Beach, for example? And I began to answer loads of questions as to why they were occurring, where they were occurring. But it was also then the simplicity of them, and I guess that is where the architecture comes in. That incredibly minimalist movement of just building a wall to trap water to enable safe access to water in an area which is challenging either because it’s got a long tide, or a rocky foreshore was just so beautiful to me. They’re just such tiny gestures making such a difference to people’s lives. And I guess as an architect, that’s what we try and do. Our work is quite restrained on the whole and I think it is about those simple moves. And some of the best architecture is the very simple, simplest gesture to improve people’s lives, whether it’s a home or a park or a gallery. I guess that was what grabbed me about them.

H: There are so many different aspects to that. One quite nerdy subject is the natural filtration system because when I’m at an indoor pool and see the lifeguards doing a pH test, putting chlorine into the water, I think about what goes into the water there. And then a tidal pool is just refreshed by ocean water (provided the ocean water is clean). The simplicity is astoundingly. I think it’s great.

CRL: It is, but what we’re beginning to realize now, because we’re now working on a new sea pool on the Isle of Wight, as well as two restorations in Scotland of 1930s pools, that the position, for example, on the beach is incredibly complex because you need to be in a location, obviously, which is just below the lowest high water mark, so that you get those two tides refreshing the water. If you screw that up, then you’re in all sorts of trouble! And there’s a good example of screwing it up in Southend on Sea where they built a new one and they built it too high up the beach. So, when it’s most in demand during the summer, when there’s less winter swells, it doesn’t refresh enough. And so, it’s just stagnant. It was literally stagnant when I saw it. And they’d spent £1 million creating this lagoon which just looked feral. I felt sorry for them, but also rather angry. To detour from that to a more positive story is Belmullet in the west coast of Ireland (page 15 in Sea Pools), which is actually one of the first ones in the book and is a fabulous example of a sea pool, which unfortunately was repaired by the council about ten years ago. And they added to the sea wall about 100mm of new concrete because the top surface was breaking down. And no one thought about the implications of doing that. So now, again, in the summer when there’s less of a swell, the water doesn’t overtop into the pool. So monthly, they have to drain the pool on a falling tide and then they get in there, the community get in, and they scrub it all down. Sometimes they bring the fire brigade along to use their hoses to clean it all out. And when that’s done, it’s beautiful. It’s an architects and engineers dream pool. I mean, it’s just a rectangle just dropped on the beach and then there’s some fabulous images of when the tide rises again and they’re doing it on a spring tide, obviously. So, you then get this incredible waterfall of water tipping over the edge, and the kids are sitting in their wetsuits waiting for it to come crashing over the top. So a bit of a problem has become a fabulous community event where everyone pulls together and meets in this sort of hybrid public space in the town centre. And that one gets me very excited, as you can see.

H: That’s amazing. That’s a really good solution to the problem. The book is absolutely incredible and each pool is a story into itself. I could go through each one and ask you questions and talk about an hour per pool. When I’m reading the book the first thing I’m curious about is whether or not they are still in existence because you’ve included some that are historical. And so there’s a curious story there. And then seeing the way that you’ve included the groups that use the pools, particular swimmers such as cold water groups, etc. So, there’s a history there as well. A lot of it goes back into the early 1900s. It’s a book where you can really get lost even on one page asking questions and thinking about the history and thinking about the location. And the images are brilliant.

CRL: Well, the images, I always told the publisher that I draw, I don’t write. So I particularly enjoyed finding the images to suit the stories which I’d found. I tried where possible to use local photographers, not professional shots all the time. And they’re very seductive when they’re from above as well. You get a real feel of the context of how these pools are positioned on the beach. So, yeah, that was a particular joy to do, I must say.

H Yes. So, I’m looking at Coal Cliff Rock Pool (pages 134-35) which is a shot looking down, and you’ve got a single swimmer doing backstroke right in the middle of the pool. And it’s just incredible with the swirls of the ocean around the rocks outside the pool. I love the mixture of a sometimes very volatile sea with waves splashing about and then the calm pool right beside it.

CRL: It also makes you think about the engineering that has gone into creating these things. These aren’t just plonked on a nice flat plateau of rock, you know, they’ve had to blast out the rock to get it in there. But it’s so beautiful in that particular image which shows you just wouldn’t be able to swim there. There’s just no access to the water there. It’s far too difficult to get into the water. Then you’ve got that tranquillity of the trapped water in the pool which is the solution. It’s very good. But also, they’re also equally amazing when they’re on a sandy beach. So, flying back to, well, we can go to Langstrand Tidal Pool in Namibia which is on the edge of the Skeleton Coast, I think it’s called the Namib Desert, the edge where the desert meets sea. It is something like a Star Wars set and they had enormous grand plans to make this into an incredible holiday resort, which never happened. It’s an extraordinary pool, and I couldn’t find any images of anyone actually using it. I kept diving into Instagram, which seemed to be the solution to most of these projects as to where to find a picture. And then I found someone who flies planes in the area and, ‘Oh yeah, I’ll go up there and take a picture for you.’ And literally the next day I had this incredible photo. So there we go. So there was a fondness to these structures, but they’re also very overlooked as well, that a lot of the time people hadn’t really thought about what they’re doing there or how useful they are for their kids to play in and are taken for granted.

H: Yes. I think the fondness and play really comes out. On pages 170-171, and I’m guessing that’s Havana, there’s a brilliant image of a kid doing a backflip into the water.

CRL: Yes. There used to be so many more along that coastline which are all underneath the road now. I’d like to go and see those ones. I must say that those look incredible.

H: How long did the research process take? You have other people contributing to the book, which is nice reading their writing. But I imagine this was quite a laborious process.

CRL: It was. The first blow to thinking I could knock this out fairly quickly is when the publishers replied to my email straight away going, this is a great idea, let’s do it. It’s the easiest book deal ever. They only had one condition that it wasn’t just a UK project, but a global project. And my heart sort of dropped. Although obviously I was deeply excited to think that there are others out there. But when I started to search them globally my OneDrive just filled up with this enormous array of pools. For example there’s 120 pools on the Sydney coast.

H: Australia seems to be particularly blessed.

CRL: And each one of them is different. Each one of them is offering something slightly different in a different context. And then South Africa again have so many of them. And particularly in South Africa, some of the more interesting ones were much harder to bottom out because they didn’t have the archives that the Australians have. And then the politics of the South African pools were particularly distressing at times, having found these incredible pools, enormous pools, like the biggest in the world, Strandfontein and Monwabisi, which are absolutely mammoth and getting very excited about that. And then just beginning to scratch the surface a little bit more and go, oh, dear. These weren’t built in the right spirit of swimming.

H: And that kills the idea of inclusivity.

CRL: I know it’s a terrible, terrible story. But it happened and the person who was really generous in helping me find a lot of the information about those was like, ‘Well, Chris, you know, that’s all history. As a nation, we’ve changed. But I think the important thing to remember here, Chris, is that these pools are loved and used by all races now. They are so much part of the swimming infrastructure of South Africa that we all love them now.’ So, that was quite reassuring. And I felt that validated their entry into the book as well. Because cutting the list down was hard, I’ve got another 200 odd pools, probably more than that, 300 or 400 pools, which I could do volumes of this book.

H: That was going to be one of my questions. Are there going to be further volumes? I think, in terms of the balance, clearly ‘the rest of the world’ has fewer and that leaves you open to volumes two, three and four.

CRL: The obvious ones are as I said, Australia and South Africa. But there are a number of other really interesting pools which could be included, particularly in the UK and the northwest coast of France. There are some amazing pools there which didn’t make the cut. I felt dreadful removing some of them. I felt like I was cutting out family members from my will or something. But, I think, yes, there’s more to be done.

H: I want to ask you about Future Lidos. I made a discovery via the website as well, of, Sea Lanes in Brighton and went down not too long ago and swam there. It was just incredible. The first day I swam was one of the many storms that we’ve had this season. And it was 55, 60 mph wind coming off the sea. And I thought, oh, they won’t be open. And I walked in and they were like, ‘no, we only close when there’s lightning’. Swimming in the pool that day, there were literally waves in the pool crashing over you. It was quite an experience. The next day I swam, it was absolutely calm and beautiful. https://www.sealanesbrighton.co.uk/

CRL: I’ve got a question then for you. Is it a lido?

H: It’s very different. It’s a really hard pool to pigeonhole. My first impression, because so many of the swimming places in Yorkshire are heavy, some of the old Edwardian pools, I’m thinking like Bramley Baths near where I live, no one is going to pick that up and move it. But Sea Lanes, it almost felt like you could just pick the whole thing up and carry it to a new place and put it down. It just seemed light in a way that was very unusual. And I know a lot of the materials they used for construction were waste recyling so everything seemed very light, but there was almost a lack of permanence to it. But I liked it. I really had a blast swimming there and the staff were incredible. The temperature was great with some people in wetsuits. I just swam in a swimsuit. It was about 18 or 19 degrees. But is it a lido? I don’t know. I never knew the word ‘lido’ until I moved to the UK. I grew up in the States and it was just an outdoor swimming pool.

CRL: I’m a bit of a traditionalist, if you’re going to use that term it’s 1930s terminology for a publicly accessible pool. The accessible aspect of it is really important. So these pools, back in the 30s, were heavily subsidized. They were encouraging people to get out and get active as they should be doing now, which they are to a degree. But, I mean, swimming is not a cheap sport to take up when you’re paying £50 a month or £12 a swim. I did talk about this with Sea Lanes, so I don’t feel too embarrassed to mention it. We think it’s a different kind of model than a lido. And, most importantly everyone’s welcome to swim there, but you pay a little bit more to swim there because it’s the National Outdoor Training Centre and the emphasis when I was there talking with them was very much training people to be able to swim in the sea. Brighton has a strong current, it’s an awkward beach. So there’s a lot to learn, potentially, if you’re frightened of swimming in the sea, there’s a lot to learn before getting in there. And I really like that. I thought that made it work because a lot of people look at it and go, well, why would you put a pool on the beach until you get there and talk to them and understand why it’s there.

I’m just a bit wary about how the councils will see it. And I know that they’re having councils visit them. Because they’re intrigued at this new model. I think from a Future Lidos point of view, I think we need to be a little bit careful that we don’t just build these things and then expect people to pay £12 to swim there.

H: Yes, I hear you. One of the first things I noticed was the price and I thought, ‘Ooh, you know, I’m living up in Yorkshire. Maybe this is just, you know, the way it is in the south.’ I was also very much aware that the setup for the pool was great for me. I’m happy going up and down all day. I like the temperature, but, it’s not a place where, at least in the winter, where you would have children just in the pool playing because unless they change the setup of the pool, because it was lanes and lanes only when I was there. I was happy, but I was almost a little bit guilty thinking, ah, this is a pool set up just for me. And what about the other swimmers?

CRL: I think to support them in their mission, they’re not pretending that it is a place for kids to come and swim. They’re just not closing the door on that. They don’t stop them coming in. But the point is, I think, is that Saltdean is open just down the road. And so you go there with the kids and there’s more facilities, more space and I think that’s why it works. It does come back to the danger of a town without a lido. Thinking that Sea Lanes is the option and that’s the bit which concerns me slightly, but, anyway, I think we’re very lucky. Very lucky with our breadth of swimming facilities in this country, particularly in the south east. And I think doing the Future Lidos group our toolkit has made me increasingly aware that although swimmers are not happy, that there aren’t enough lidos, we’re actually pretty well resourced with our coastline, our lakes, our rivers, all of which we can get into in a lot of places. And we have a reasonable amount of pools, you know. We could have more, where we’re short of pools, in areas that need pools, particularly the north of England. This was further emphasized to me when I went to Sydney. We at Studio Octopi were doing some work out there establishing new swim sites in the harbour, which was a brilliant job, probably the best job in the world. And I went there and I was astounded to see that the East Coast, obviously the beaches, we know Bondi and all of that, and all the ocean pools along there. The ocean pools are spectacular. You couldn’t dream of anything better. And you go into the city centre, and you have a good resource of pools, outdoor pools, and they’re lovely. They’re beautifully done. But it’s the further west you go to Parramatta and to the western Sydney suburbs. There are no pools. There’s no access to water and less pools. And inland, Australians generally don’t swim in their inland waterways which is also because the majority live in coastal cities. So, I was astounded by that because we always assume that Australians are completely on top of swimming. But actually the mere fact that Sydney Water, the equivalent to Yorkshire Water, Thames Water, was doing this project to explore where new swim sites could be set up prove to me that actually they don’t access enough of their water. And actually, although we have other issues at the moment to do with pollution, we don’t have too bad a setup if we can just get those water companies sorted and more lidos, we would have a wonderful setup.

H: Yes, it’s interesting here. I vacillate between swimming in the River Wharfe sometimes and then just deciding that I don’t want to swim in the river. I’m just not that happy with what’s floating down. It’s interesting in Ilkley, they fought really hard to get that a designated bathing spot, but I still think the quality of the water has a way to go.

CRL: I fear it’s decades, to be honest. Yeah, it’s all a bit grim. It shouldn’t be a situation where after it rains, we can’t swim. I mean, that’s just bonkers, frankly.

H: This is a kind of a backing up question, but, the Future Lidos Group. So, the mission there is to work together with different members of communities that are trying to establish or re-establish a lido in a particular area. I mean, is that too simplistic a description? https://www.futurelidos.org/

CRL: That is the overarching essence of it. That’s where it started. It started on the back of the book which identified all the lidos across the country. (Pusill, E & Wilkinson, J. 2019 The Lido Guide. London: Unbound) and the National Lido conference, which happened, I think, a few times. Then there was a gathering of some of us to talk about how we might try and bring everyone together, so now it is a loose network of probably 40 to 50 different campaigns across the country and Ireland. All of which are at different stages of trying to establish a new swim site. I mean, it’s called lidos predominantly, but that includes new sea pools, I think we’re drawing the line at setting up swimming in rivers, new sites for rivers. But in theory, it does include anything which increases safe access to water for swimming. And so we have a series of online meetings quarterly or monthly, where people can come in and join the Zoom call chat. So people bring problems to it. There’s an open discussion. Sometimes we have people presenting some progress on their project, or outsiders talking about how to do stuff and it’s a place to share resources and all of that data is now going into an online free-to-access toolkit. We got funding from the National Lottery, to do this, just under £100 K. And so we’ve been developing this online toolkit which will allow, Mrs. Jones, in Macclesfield to have a quick look at this site and go, is it viable for me to propose my swimming group, try and refurbish this lido or build a new lido here and it’ll have site appraisal, is the site even big enough? Okay. What do I need to look at? Okay. No, it’s not big enough. What do I need? Oh. Land ownership. There’s a good point, and it’s little prompts through this thing. And it’s all going to be hyperlinked together so you can hit land ownership that will take you there. It’s unbelievably complex, to be honest. We’ve written 72,000 words between the five specialists. I’m in charge of design. We have an environmental specialist, a business specialist, and an advocacy and community engagement specialist. And so we’ve written far too many words which we’re now trying to edit down. But it will be the first resource as to how you go about delivering a new outdoor pool. Swim England, Sport England have never done anything like this. They’ve both been very supportive of it, and I think it’s a stepping stone. I mean, we’re not going to be able to cover everything on it, but it’s a start as to how to give communities a leg up to doing something within their community, within their neighbourhood, to improve their access to water.

H: That’s brilliant. And looking in from the outside, it is a complicated process I can see. All the different stages of what can go right and what can go wrong. I was following the campaign organised by Caroline Kindy and the project there and the unsuccessful auction and then I’m aware of where I live in Otley. They’ve been trying to re-establish the Lido there and I really have my fingers crossed and would love to see it. But I can see again from the outside, questions about access to that particular location where the pool was in the past and the way the environment has changed over time with traffic and bottlenecks. And I think, is it really going to work there the way it was before? I can imagine it’s such a difficult process to either re-establish or get a pool started.

CRL: Yes it is. And I think the bit which I found particularly challenging is trying to make it very simple and accessible. It’s helped me focus on quite how complex it is for when someone says, “Chris, here’s a site for a pool. Does it work?” It isn’t just a five-minute job where you just go, yeah, it could work. You’ve got levels, you’ve got overlooking, you’ve got an aspect, you’ve got so many different factors. And that’s before you get into the technical regulations about what is permitted or not permitted or the financing. So, in a way I feel better, our job is quite hard. But, the focus of the toolkit is also about getting a design team around who can help the campaigners through this. The danger is that a little bit of information is quite dangerous because these community groups think that they can build it from this toolkit and in a couple of months. Well, I thought I’d build Thames Baths in a year.

H: Well, it’s been fascinating talking with you. Thank you so much

A Conversation with Joe Stanhope: Jubilee Park

Haynes: Thanks so much for the chance to talk with you today. Can I just start by asking about Jubilee Park?

Joe: It was originally given by a wealthy lady, Lady Weigel, and she gave it to the people of Woodhall Spa in 1935. In the recent years, it had been run by council and had gone through a fairly typical process where the council had said it was unaffordable to run. It was losing hundreds of thousands of pounds of taxpayers’ money. About 15 years ago it was passed over to the parish council, who ran it for five years, and most parish councils aren’t set up to run a business of this size. That became fairly apparent, and they assisted in the generation of a completely separate charity that has now been running it for nine and a half years. I first got involved as a 16-year-old cleaner and lifeguard which is about 18 years ago now and I’ve been here ever since. So, I did what a lot of our staff do in that I spent years between university and A-levels working seasonally. And then as I was coming to the end of my university degree, I was offered the opportunity to be the first year-round kind of person and I thought to myself at that point, yeah, I’ll give this five years and 13 years later, here we are. So that’s how I got involved. I’ve always been a swimmer. I swam competitively and I also played ice hockey at a very high standard. So, leisure centres have always been something that I’ve been involved with and I kind of stumbled across this purely by accident when I was looking for a job between gap years, and here I am.

Haynes: I think the kind of stumbling into things resonates with my own life as well. I’m really interested in your role because I think it’s easy to go to a pool and jump in and have a swim and go home and not kind of think about all the work that goes on behind the scenes. So, I’m wondering what some of the biggest challenges are that you face in terms of keeping a pool running and making sure everybody’s happy and can swim the way they want to.

Joe: So, Jubilee Park is a seasonal pool. It’s open for six months of the year. We’d love to have it open all year, but there are a number of challenges around that. And Woodhall Spa is based in central Lincolnshire, which if you’ve ever been to central Lincolnshire, it’s the back end of nowhere. We have a population mass within ten miles of about 60 or 70,000 people. And if you compare that with any of the other large lidos across the country, they’ve all got ten, twenty times as many people as that within a ten-mile radius, because they’ve all got cities that they’re associated with or right next to. So one of our key challenges is that we have a very small population mass to service our facility and particularly the lido. And as such, we’ve had to do things slightly differently to how a lot of other places operate. So we use more of a tourism-based model in that Jubilee Park is a destination and that doesn’t mean that we’re not here for the community. We absolutely are. But until recently, the community really only made up for 5 to 10% of our usage which obviously doesn’t pay the bills.

And coming on to bills, which is probably the next biggest challenge. Bills for a swimming pool are massive and there’s very few ways of getting away from that. In the past few years they have doubled. Tripled. Just gone up and more than any expectation that we ever had. And so when you break down our running costs per day, which would include staffing and heating the pool, electricity to pump the water around, filtration systems, chemicals. When you take everything into account you’re talking over £2,000 a day to open staff, heat the pool. And in comparison, when you think that a swim is between £7 – £9 with us, which is more than most places, that’s a lot of £7 swims that you’ve got to get through to just break even. So that is a real challenge in a time when everybody’s really feeling that money is tight. And, you know, a swim 15 years ago at £3 and a swim now at £7 to £9. Well, my wages haven’t tripled in that time, and I don’t think many peoples have. So swimming is no longer a cheap activity and that does present a challenge for us. The other side to this is staff. Leisure swimming pools, have a need for a large number of staff and a seasonal pool presents an even bigger issue in that seasonal work only really meets a certain demographic or typically a certain demographic.

Yeah, and in that mostly it’s aimed at youngsters or students. I would say over the last 15 years that demographic of people have wanted to work less. As such, you end up having to employ more staff, but also that the staff who are coming are coming to us with far less skills. A 16 year-old coming out of school today requires far more training than a 16 year-old coming out of school 15 years ago. So you’ve almost got an issue at both ends in that these staff don’t want to work as much. They’ve got a better social life or I’ve never quite worked out why they don’t want to work as much, but they don’t. Then you’re having to train them even more. So it’s more cost associated with the business and bringing these people together. I think in a nutshell, those are the key difficulties for us in that there are lots of little things going on, but those are the big ones.

Haynes: That sounds immense. It’s huge challenges everywhere you look. If it makes you feel better, I’ve just gone down to Brighton to swim at Sea Lanes, which they’ve just opened along the coast, and that’s £11 a swim. If you live in Brighton and you’re a member, it’s cheaper. But £11 you’re just rocking up. I did get the over-60 discount though, so I was happy about that. I’m thinking about heating the pool. Do you aim for a general temperature? I guess if you’ve got hot summer days, you’re helped by the sun. But I imagine that’s it’s a massive cost in terms of keeping the pool heated.

Joe: So our pool and our paddling pool are heated to 29.5 degrees, not 29.4 and not 29.6. It is balmy for a reason. And that reason is that we need everybody to understand that Jubilee Park Lido Pool is going to be a nice temperature, whether it’s snow, wind, rain, whatever. 15 years ago, if we had a rainy day, you’d maybe get 2 or 3 swimmers in in the entire day. But you’ve still got all your running costs. You’ve still got that. And these days, a rainy day has three, 400 people coming swimming. And that’s one of the keys to making Jubilee Park work for us, is that we’ve really trained our customers that you can still come on these days and a lot of them only come now when it’s raining.

Haynes: I love swimming in an outdoor pool when it’s raining. I guess it’s about knowing your customers as well. I mean, going back to Sea Lanes where I’ve just been, they stay open year-round, but in the winter it’s about 19 degrees and so it caters for a very limited kind of swimmer. I’m that kind so I’m happy. But again, it’s got a big city to draw on. I was just looking at the reviews of Sea Lanes and there’s clearly a group that’s unhappy with that temperature and who complain that it’s too cold. So it’s difficult just trying to find that happy medium to be able to cater for different people with different kind of preferences.

Joe: When I’ve worked this out over the years, if I drop the pool temperature by one degree, I lose babies. That means babies can’t come and swim. Yeah, okay. Well, you know, 25% of our demographic that come are families that involve babies or very young children. So if I drop it one degree, I’ve lost 25%, give or take a bit. If I drop it three degrees, I can’t run any swimming lessons whatsoever. Well, swimming lessons make up for one-fifth of our income. All right, so let’s talk about if I run cold water, so completely cold water and I lose 80% of our demographic, now 20% of a million people is quite a lot. But 20% of a very small market and isn’t. And that’s how places like Hathersage or places in London, stay open. People compare us to Hathersage, but Hathersage is on the outskirts of Sheffield. And if you looked at it, you’d think, oh yeah, it’s middle of nowhere, but it’s a ten, 15-minute drive from the centre of Sheffield. And, Sheffield is a sports city. You know, the facilities there are incredible. And they’ve got a real good base of people if they want to run cold water sessions but the centre of Lincolnshire, not so much. And that’s why we’ve had to take this slightly different approach. I would love to run Jubilee Park at a cooler temperature. My favourite lido is Sandford Parks in Cheltenham and they run theirs at 26 degrees which is perfect for properly swimming without a wetsuit and without having to worry about how long you’re in the water. So you can go in, you can train and most people find that comfortable. My daughter, who’s six, would get in and enjoy an hour on a summer’s day. But it does knock out a big demographic. And when you really need to cater for all of that demographic that’s why we got to do it.

Haynes: Yeah, I understand completely. I mean, yeah, it’s interesting with Hathersage, I’ve swum there a couple of times, but I find it difficult because it’s in such demand that as somebody who doesn’t live in that area, it’s difficult to find an available slot because it is just booked up completely. Do you have local schools in the area using the pool for their swimming lessons?

Joe: We do. We do two types of swimming lessons. We do our own ‘learn to swim’ programme and during the winter months, we take that over to a small school pool just so that we keep that going. We also run swimming lessons for schools. Now we do those at cost and we don’t make any profit out of that because we think that’s the right thing to do. But also in reality there is a small sales tactic there in that the kids come and they say how amazing it is and we need that support and that involvement. So we teach over 300 kids from schools a week. And, we have about the same number in our ‘Learn to Swim’ programme.

Haynes: That’s fantastic. I mean, that’s incredibly important, just to have children at school being able to find a pool and be able to have lessons. The pool that I tend to swim in at the university where I work, they have about 5 or 6 schools that come in regularly and they just split the pool. They keep some lanes going, but they have children off on the other side and it’s great seeing them learn how to swim.

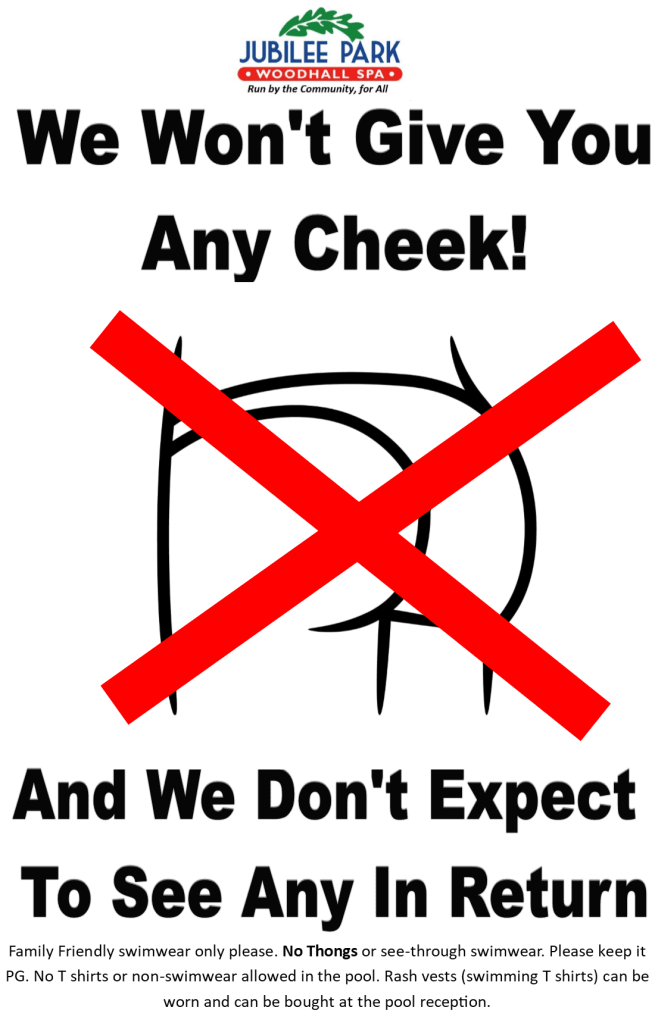

I was speaking to you a few years ago at Bramley Baths (Leeds), and I’m pretty sure this is right, but correct me if I’m wrong, I was interested at the time because I was doing some research about women in France who were campaigning for the right to wear ‘covering’ swimsuits, sort of more ‘modest’ swimwear (than allowed by the municipal council). And I think I remember talking to you because you had pool signs that were addressing the opposite. Saying essentially that you were discouraging swimmers from wearing almost nothing at Jubilee Park.

Joe: You are right. So it’s really interesting and probably things have changed ever so slightly since we last spoke about this. We were finding that there was a ‘Love Island’ effect. And, we found that as ‘Love Island’ became significantly more popular, we were finding that bathing suits were becoming more and more skimpy, particularly thongs. And at the time, thong swimsuits weren’t commonplace in British swimming pools. And in fact, in all the years I’ve been around swimming pools in the UK, and I hadn’t come across it until the Love Island effect took hold. And while I was aware that it was a thing in Europe, it just wasn’t a thing here. And so we started seeing this and we started finding that we were in situations where there were more and more issues where people were saying, “That’s not appropriate”. And, at the time, you know, we agreed with that. Not only females, but males and you know the thought that somebody is wearing a see-through swimming costume, that also happens. So we came out and we created these signs that basically said, “Our lifeguards won’t give you any cheek, and we’d rather not see any in return.” That’s it, with a cheeky photo sort of thing on it, a computer-generated photo. And we created a bit of a national debate really in The Sun newspaper and other newspapers about what is appropriate and what’s not.

And, you know, it was a very divided opinion at the time. And over the past 3 or 4 years, as we’ve dealt with it more and more, it has actually become more commonplace. And while we don’t encourage it at all, we also don’t challenge it anymore. And we don’t challenge thongs in particular. Other things we make a judgment call on, but we don’t find that we have the complaints that we once did, and partly because it’s become more normal in society. And certainly, you know, what would have been 1 or 2 people wearing it on a very busy day five, six years ago and is now 50 people wearing a swimsuit like that. It’s interesting how people’s perceptions have changed in such a small period. And, I think Love Island and similar TV shows to that are becoming more and more commonplace. I also think that people have understood what our key issues were, which is, at what age is it appropriate to wear a thong swimming suit? A 13 year-old doing that and a 30 year-old doing that? And should there be a difference and is there a difference? I think people are just naturally coming around to the idea that these things are our issues and we’re starting to be a bit more sensible about them, but we’re also becoming more accepting of what’s appropriate and what’s not.

Haynes: Yeah, it’s a difficult arena. You know on top of the £2000 plus running cost a day and then having to get into that as well is not easy at all.

Joe: One of the things we found is that for our male members of staff, talking to a female about whether their swimwear is appropriate is one of the most difficult conversations you can possibly have. And one of the reasons that we’ve stopped challenging it, unless it is really inappropriate, is for those reasons.

Haynes: Yes, definitely. The last area that I was hoping to talk to you about is the ‘Donate a Swim’ scheme, which to me sounds like just a fantastic idea. Can you tell me a little bit more about that?

Joe: So ‘Donate a Swim’ came about for two reasons, really. The first reason was I was very aware that a swim at our pool – and our pool in particular, because we’re not funded by government or council, we don’t receive any funding towards our running costs, we’re completely self-sufficient – because of that, our costs have continued to rise. And the cost of a swim as we were saying earlier is three times as much as it was 15 years ago. And 15 years ago, we still had swim for free schemes by the government, for children and everything else. So, I was aware that the cost of swimming wasn’t affordable for a large proportion of society. And I was also aware that actually Jubilee Park, and outdoor pools in particular, offer a real benefit for people suffering with their mental health. And we’ve seen a large rise in either the reporting of mental health issues or in mental health issues since Covid. I was aware that everybody has been told the best things you can do is be outdoors and exercise more. Well, the swimming outdoors is probably the best thing possible for that situation in a lovely environment like Jubilee Park. And I was trying to think about how we could help these people. I saw the ‘I’m putting a coffee on hold’ scheme and I thought actually, we could do that with a swim. We came up with the idea that Jubilee Park would subsidize swims, and people could then buy them for somebody in need. Obviously there’s nothing like this, or certainly we’ve not ever found anything like this, so we’ve had to implement it all ourselves. We’ve put a donation system in through our website where people donate swims, and then we have an application process which we’ve made as straightforward as we possibly can. And it’s interesting because we’ve looked at loads of different pots of funding for this, and we’ve almost made this application process too straightforward because we can’t get any funding for it (from outside providers), because we can’t collect the data that they require. But the flip side to this is that if you’re in need of a swim, do you want to be applying and giving your data and circumstances? You don’t want a complicated process because you’re either very embarrassed about the process or you’re maybe not in the right headspace? And so, there’s a very simple, straightforward process that we then administer in-house.

One of our team would give a call or an email, depending on what this person decides and books them in at an appropriate time. And we do that because if somebody’s suffering and we don’t know what they’re suffering with. But if somebody said that it’s for mental health reasons and we’re maybe not going to put them in on the busiest swim of the year, we’re probably going to put them in on a much quieter swim. However, if it’s that they can’t afford for their family then it’s pointless us putting them in at a time that’s not suitable for their family. So it allows us to hopefully tailor this a little bit to the person’s needs and create the best possible experience that also fits in with the organisation, and it’s pointless organising people on the busiest day of the season. And so we’ve been running it for a couple of years now, and we’ve amassed or had donated just under 400 swims, and we’ve used just over 200 of those. Now, the reason we’ve got quite a lot of them in it is we had a family who donated a large chunk of swims and in memory of their son who committed suicide, and the family were very close to the park, and a really nice way of remembering that person. So they will be available next year and to pass over to other people.

What we’ve found is it’s worked really nicely. We’ve not had a time where we’ve not had a swim for someone in need. We actually started this just before the Ukraine war, and we had no intention that it would be used for Ukrainian refugees. But actually we found that straight away that’s a large proportion of what it was being used for, in that a number of Ukrainian refugees were coming to the area with nothing and were trying to get started. They had seen horrific things and needed some help and support, and this was one of the ways that they did it. And, so a good proportion went to Ukrainian refugees. We’ve also worked with mental health charities, and we’ve had a couple of times where they’ve organised a bus or a minibus of smaller groups to be able to come and use on this scheme. And it’s worked really nicely and it’s meant that if somebody is struggling and we’ve known times when people are really struggling and we’ve been able to just say to them, okay, this is here, you can use this and, don’t feel that you can’t. And that’s exactly what it set up for. And that has then helped those people to get back on track. We’ve had some really nice comments come back from it.

Haynes: That’s absolutely fantastic. I was thinking last night around the practicalities and that there would be some sort of delicate aspects and how do you actually match up the people with the free spaces. But it sounds like you’ve put a lot of thought into it. And it’s a simple process. Maybe you need to be made ‘Swim Czar’ for the UK and be in charge of rolling this scheme out nationwide because I think it sounds brilliant.

Joe: I think I was a little bit shocked that there was nothing similar to this scheme going on. It would be great to put it out. I’ve spoken about it at a number of the ‘Historic Pool’ events, but also at community leisure events and other things. It’s open for people to use, and the beauty around it is that it really gets the community involved. We’re one facility and in one facility there’s been 400 swims donated. It’s not masses, but it means that for the people who need that support and need that, it’s there. From our point of view, we would always run something to try and encourage more people to come and use the facility. And by doing it this way, we’re doing that. But we’re also involving the community in that. And that’s very powerful.

Haynes: That is great. Well, I think that’s all of my questions, so I really appreciate your time. It’s been a pleasure talking to you. I could talk to you for another 2 or 3 hours, but I know you have a business to run. Thanks so much.

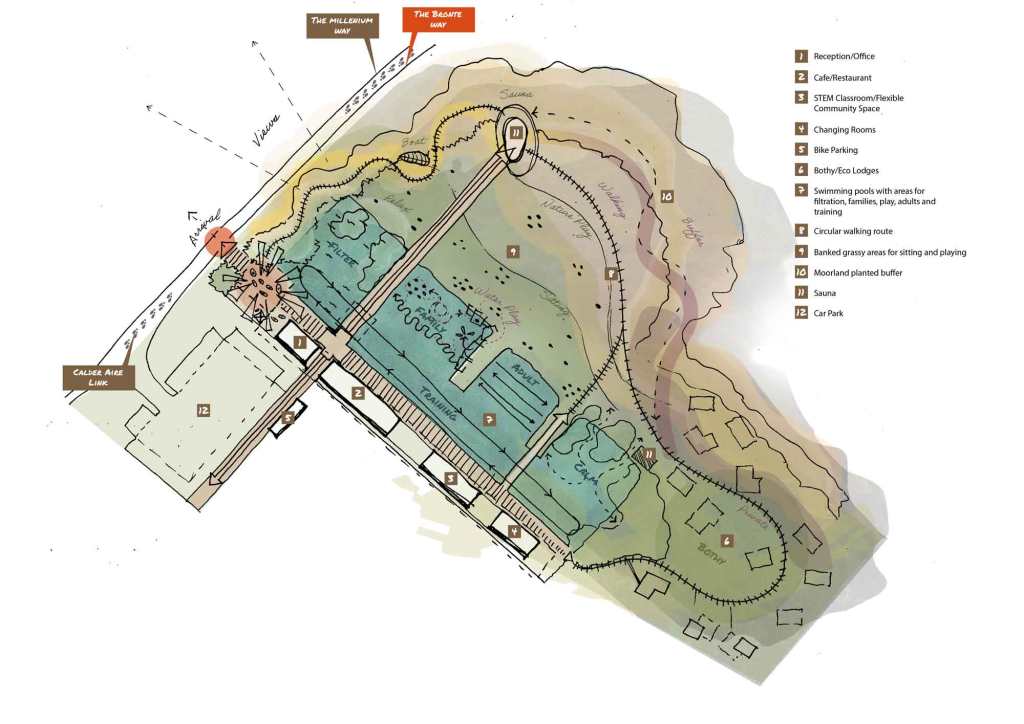

Caroline Kindy: Yorkshire Swim Works & Future Lidos

Haynes: Okay. Well, let’s go back to the beginning [of Yorkshire Swim Works]. So, there’s a really lovely story about standing on the side of a moor and imagining a lido in one of the old reservoirs. Was that your inspiration?

Caroline: Yeah, exactly. So, during lockdown three years ago now, you know, I am an outdoor swimmer and I love looking for interesting places to swim, safe places to swim. And there aren’t that many around where I am. You have to kind of travel fairly far and you kind of end up swimming in places you’re not really meant to swim in and so, yes, I was stood at this site, which is a former water treatment works. They have these incredible Victorian built sand filtration basins and yeah exactly that, about this time of year, three years ago I was stood in one of those basins and I just thought, wow, this could make an incredible location, an incredible experience for people to come and swim in.

Haynes: It’s a brilliant idea. And I’m with you all the way in struggling to find places to swim. I’ll swim anywhere, basically. But I do like swimming outdoors a lot. I’ve been going to the Lido in Ilkley, which is about six, seven miles down the road from where I live. I was there this morning, and it was absolutely gorgeous. But equally I’ll swim in the Wharfe River. But there’s always a problem with pollution and cleanliness and so I’m a bit cautious there. So, I love the idea for the site there and I was really interested in all the things around it. It was a really an innovative idea, the idea of a swimming lido with no chemicals. And I really like the examples of other places as well that you showed on the website. Yeah, absolutely brilliant.